Like documentary filmmaking, podcasting is an exercise in creative problem solving. From honing the pitch of your series to boiling down what each episode is really about, every step of the way comes with its own challenges and rewards.

Being a documentary filmmaker has taught me a few things about podcasting that will hopefully help you on your journey: remove your crutch, become a student of structure, and reimagine your role as an interviewer.

Remove Your Crutch

In documentary filmmaking, my crutch was cinematography. Every project I become more and more obsessed with how the film looked and lost the “why” of the project: the story.

In any creative medium, we can develop a creative crutch. It’s a thing we lean on that makes projects a little easier but keeps us from getting better at the more difficult (and often more meaningful) aspects of our work.

Around the time I was having this realization, I was in between flights on my way to film a short documentary in Nevada. My phone buzzed. It was my friend Anna.

“Have you ever considered doing a podcast?” she asked.

I hadn’t really considered it. However, a podcast would remove my crutch of visuals completely and force me to focus on storytelling. It was a scary, exciting challenge.

A few weeks later I dove in. Stripping away my crutch refocused my creative lens and helped me grow as a storyteller. The moral of the story is to beware of your creative obsessions—they can be crutches disguised as “the way.”

Become a Student of Structure

Whether you’re creating a podcast on finances or documenting a murder investigation, you need structure. After all, it’s not just what you say, it’s how you structure it.

I used to think structure was the death of creativity. But after being a one-man band for documentaries, I realized that structure is one of the greatest tools in a storyteller’s arsenal. When filming, if I didn’t go in with a structure in mind, I was guaranteeing myself an extra ten or more hours of editing I’d need to do, because I’d have to wade through the footage to find the story…if there even was one at all.

It’s not just what you say, it’s how you structure it.

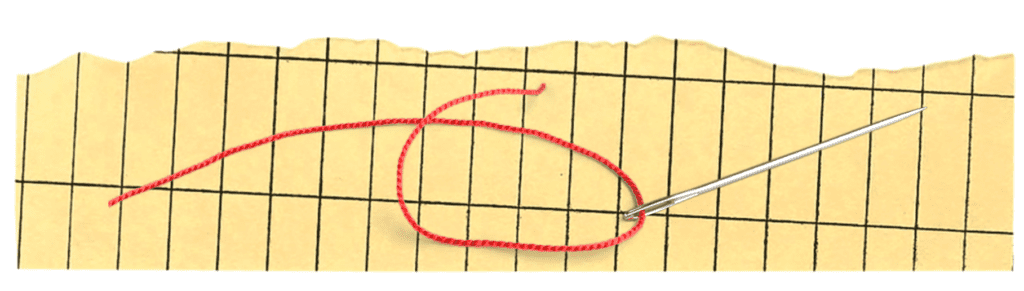

One structural method I really enjoy is the ‘red string.’ This is a narrative device in which you break a story into three parts (or more) and scatter those parts throughout the episode. Each part, except for the final piece, ends on a cliffhanger, leaving the audience wondering what happens next. This gives momentum to your episode and (hopefully) festers a curiosity in the listener.

To help better explain this method, here’s a real-world example of how I used the red string in What We Do.

The red string came in handy for a podcast episode I produced on the story of how Bob Bergen became the voice of Porky Pig. I had an armful of great anecdotes and moments from the interview to choose from. But when put together, they felt more like a collection of stuff rather than a cohesive story. So I started looking for a red string.

Part 1: Search and Discover

I didn’t see a strong enough one within the interview pieces. Then I remembered seeing on his website an audio clip from when he was young. It turns out this audio clip was an actual recording of him calling Mel Blanc (the man behind tons of animated characters, including Porky Pig). It was a little nugget of gold I listened to and broke down into three parts:

Bob goes through the phone book and eventually finds the number for Mel’s house. His wife picks up. Mel isn’t home. But Bob is elated because he’s finally got the right number. Mel’s wife lets Bob know Mel will be home later. Bob’s left to wait for a few hours until Mel returns home.

Part 2: Touching the Dream

Bob calls back. This time, he gets Mel on the phone. Bob is ecstatic to finally be talking to him. Mel’s first question: “How’d you get my number?”

Though their call gets off to a rocky start, Mel soon warms up and gives Bob a master class on voiceover theory. We hear the first part of their conversation, but I didn’t want to play the whole thing. I needed to step away at the right time to leave the listener wanting more. But how do I get out of the call in a way that feels natural in the moment and fits the narrative?

Here’s how I decided to do it: This call with Mel was technically Bob’s first audition, which is a far cry from the quality of the auditions he does today. So we move from that reflection from myself to a clip from our interview where Bob talks about auditioning. And like that, we’ve stepped away from the red string momentarily.

Part 3: The Long Road Ahead

Bob is motivated to become the voice of Porky Pig, and Mel is happy to entertain his questions. With that teaching comes a hard truth: There’s a long road ahead. “It takes an awful long time to get established,” Mel says.

We hear the first part of their conversation, but I didn’t want to play the whole thing. I needed to step away at the right time to leave the listener wanting more.

With that line, the red string is complete and we float into the final scene. Bob is older and after years of practice, he gets a call to be on “Tiny Tunes.” The red string provided structure, as well as a built-in way to bring forth the conclusion of the story.

Reimagine Your ‘Roll' as an Interviewer

Sitting face-to-face with an interviewee is tough, especially in a documentary setting with the camera rolling. There’s lighting, framing, sound — as a one-man band, the process can be nerve-wracking. After all, if any of those elements bomb, it’s your fault.

It took me a handful of interviews (and hours of shaking my head in the editing room) to realize the truth: None of those things matter if the interview isn’t fruitful.

One guaranteed way I found to fail the interview is if I just played the part.

If you see an interview as two opposing roles — you, the one who asks questions, and the guest, the one who answers — you’re missing out on an opportunity to truly connect. If you want a memorable interview, I think there’s a better way. And it starts with intent.

If you see an interview as two opposing roles — you, the one who asks questions, and the guest, the one who answers — you’re missing out on an opportunity to truly connect.

Don’t go into the conversation with the aim to respond. Go in with the motive to understand. (Celeste Headlee gave a great TED Talk on the subject.) It’s your job to create an environment in which the interviewee pries open their vault of knowledge and lets you shuffle through the files.

Always be curious. Dig into the subject prior to the interview (as an example, I devote 2-3 hours of pre-interview research). And dig into the subject during the interview as well. I’ve found that if I’m present in the moment and having a conversation with the intent to understand, and my curiosity is firing on all cylinders, I am proud of the outcome. Plus, the interview is a helluva lot more fun.

If the words we use to describe our experiences become our experiences, then perhaps we should shift from “interviews” to “conversations.” That way we approach every interview with the same open mind we have when we’re connecting with a friend.

Key Takeaways

- Creative crutches keep you from improving.

- Mastering structure provides creative freedom.

- Unless you're a cat, curiosity is a great thing.

- Don't conduct interviews. Have conversations.

Join the Movement